When we first started making bread, overproofed dough was probably my biggest worry. I can remember just feeling like I was in the dark about knowing when dough had proofed enough and when to catch it at the perfect time. Which is how we got to this blog post, as I wanted to know what my options were if my dough overproofed. I ultimately wanted to know if knocking it down and letting it rise a third time would be okay?

We actually have an entire blog post that walks you through knowing when bread dough is done proofing. If you feel like you’re in the dark, we’re confident it will clear some things up for you.

But don’t click away too soon, as we’ll almost certainly be able to put your mind at ease about extra rises. At the very least, you’ll be armed with more information and more options.

When common ratios of ingredients are used, bread dough made with commercial yeast can be knocked down and left to rise upwards of ten times. However, for best results, most bread dough should be baked after the second rise but before a fifth rise.

I know it is hard to believe that dough can rise nearly ten times. But, given our tests and research, it’s true. We’re not saying you’ll always get ten rises, nor are we saying it is practical. Just that it is possible.

For example, if you leave your dough to rise and go on vacation for a week, you’re not going to come back to knock it down and have it rise. It’s done for at that point. So time matters here, as it primarily has to do with yeast consuming the available nutrition in the dough. It will eventually run out of nutrition.

But, if your room got too warm during proofing, and you walk in to see your dough has overproofed in the hour that your recipe calls for, you’ll be just fine to knock it down and see it rise for a third time. If you keep up that rate, you’ll likely see something close to ten rises.

But you wouldn’t want to get anywhere near ten rises, to be honest. It takes all day and results in less than desirable bread.

We recently recorded a time-lapse video where we let a small batch of dough rise eight times before baking it. The finished mini loaf of bread looked fine, but it was so bitter we couldn’t palet it.

You can see the little test we did in the video at the end of this post, along with our thoughts on it.

But let’s address some added questions you might be having at this moment. 🙂

If you’re like me when I first heard this I wanted to know why so many recipes suggested two rises if yeast can go much longer. And certainly, you might be wondering why there seems to be so much pressure about catching dough before it overproofs.

Let’s address each of those separately.

Why do Recipes Call For Two Rises?

If you’ve looked at any number of recipes for basic yeasted bread, you’ll almost certainly see ALL of them calling for two rises. It’s true that some varieties of bread like brioche call for three, but basic loaves almost always call for two rises.

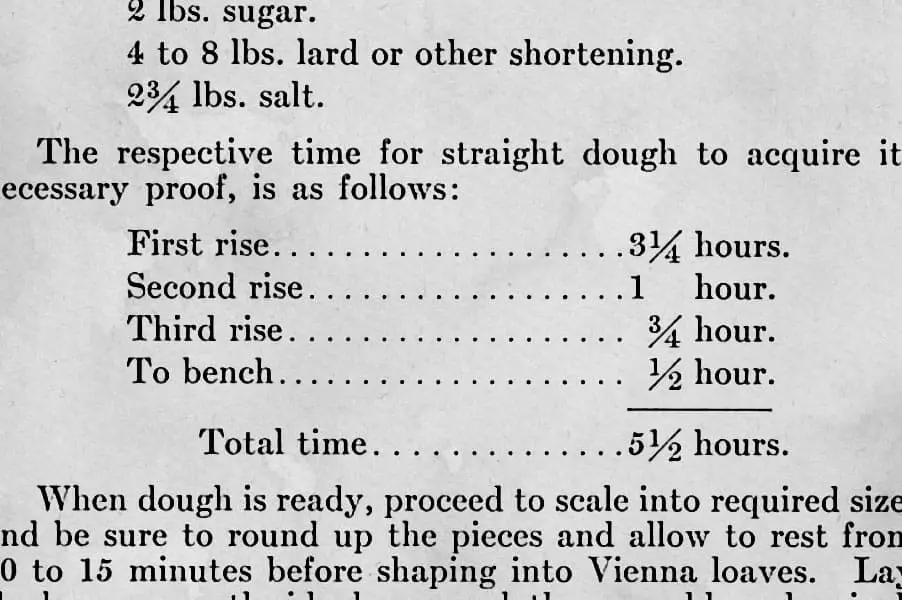

The interesting thing with this is that not that long ago (at least compared to the history of bread) many common bread varieties were regularly given three rises. I’ve really been enjoying reading through bread books from the late 1800’s and early 1900’s and have been surprised to see just how many recipes call for three rises.

We don’t really know why three rise periods have mostly gone away leaving two rise periods as the modern standard, but we assume it must have something to do with modern varieties of commercial yeast.

But what we can address is why modern yeast bread is given just two rises. The simple answer here is that two rises are all that most bread dough needs. Anything past two rises will not result in better bread.

If better bread is desired, slowing down each of the two rise periods by using less yeast, a bit of salt, and/or lowering room temperatures is the better option. Adding more time via extra rise periods can actually have diminishing returns. This is especially true if you go past three or four rises.

The short of it is that more than two rise periods would be a waste of the baker’s time invested in most bread. And once dough is knocked down more than four times there is ultimately a negative return on taste, texture, and size.

Why do so Many Warn About Overproofing?

If dough can simply be knocked back down and given a third or even fourth rise before things really start to decline, we might wonder why we are warned about overproofing so often.

The short of it is that overproofing is really bad news for bread. It results in many undesirable attributes of failed bread. Overproofed dough that is baked can result in collapsed bread, dense bread, lopsided loaves, tearing, blow-outs and more.

It should be noted that some of those attributes above, such as collapsed bread, are the result of severe overproofing. Dough that is just slightly over, isn’t going to result in disaster. But none the less, we want to avoid baking overproofed dough.

In short, avoid BAKING overproofed dough, and avoid SEVERELY overproofing dough. If you can avoid those two things, you’ll be just fine. Overproofed dough, especially if it is just the first or second rise, can always be knocked down and given another rise.

But be careful, don’t let your dough become extremely overproofed. If your dough has become so overproofed that it cannot hold any tension, it is nearly impossible to salvage it and turn it into a light and fluffy loaf. You’ll recognize it right away, as it will just fall apart as you attempt to shape it. The best way to describe it is like liquid magic sand.

In all of the loaves we’ve made over the years, we’ve only had that happen once to a batch of sourdough, using a very low protein (therefore low gluten) flour that sat in 90° F temperatures for 6 hours. If you’re not sure why we said low protein equals low gluten you can check out our post on bread flour, protein, and gluten here.

We salvaged the sourdough by adding a little extra flour and water until it was able to hold its shape. It was a bit dense and ugly, but it was delicious with butter. 🙂

Please note here as well, that sourdough is another thing altogether for rising stages. It is not nearly as robust as commercially yeasted dough. If working with sourdough, you’ll need to correct overproofing in the first rise. The second rise is not very forgiving.

Dough made from commercial yeast on the other hand, is more than fine with being knocked down a third time, and if you absolutely have to a fourth time.

And if you have to do it a 5th time, for the love of bread set a timer or something. 🙂

Our Simple Test

To run our little test, we made a batch of basic white bread but scaled it down using baker’s percentage. The loaf ended up being a 60 percent hydration dough using 100 grams of flour and 1 grams active dry yeast.

Starting dough temp was 70° F and average room temperature was 81° F.

Time To Double

| Time | Doubled Yes/No | |

| Rise 1 | 40 min | Yes |

| Rise 2 | 35 min | Yes |

| Rise 3 | 45 min | Yes |

| Rise 4 | 60 min | Yes |

| Rise 5 | 65 min | Yes |

| Rise 6 | 80 min | Yes |

| Rise 7 | 120 min | *Yes |

| Rise 8 | 75 min | Not measured |

Discussion

We were surprised with these results, as we’ve never let dough rise this many times before. We’ve gone four times before, but never beyond that. I fully expected the rise period after four attempts to be much longer. Even a two hour rise on the seventh attempt was much shorter than I was expecting.

Additionally, the finished loaf had much better texture than I anticipated and even a bit more oven spring. I certainly was anticipating a much more dense loaf of bread than we ended up with.

The major downfall here was the taste. The yeast/alcohol flavor notes were extremely bitter. It was not palatable, and trust me we are not picky eaters in this house. 🙂

*We are certain this could have gone at least one more round, but we decided we would stop this experiment once a new rise struggled to reach the previous mark. In this case, on rise number seven, the dough failed to reach the volume of rise number six.

But, let’s be honest here, the likelihood of anyone needed to let dough rise this many times is slim to none. If you need to do a third or fourth rise, you should have confidence that you’ll end up with a decent loaf of bread. It might be more dense than desired, but depending on conditions, you might see no difference at all.